There is a needless debate within some movements about supposed Babylonian origins of the upcoming Leviticus 23 Fall Feast, which goes by the names of Yom Teruah and Rosh HaShanah, but in reality, is never formally named in Scripture. Unlike Pesach (Passover), Shavuot (Pentecost), Yom Kippur (the Day of Atonement), and Sukkot (the Feast of Tabernacles), the first day of the Biblical month of Tishri is in many ways described but never actually named. It is described as a day of shouting or of the sounding of the shofar (translated “trumpet” in English), but it is never actually given a name–which is why it has been labelled by people with names suited to its function in both the religious calendar of months, and the agricultural/civic calendar of years. It therefore has no wrong names, just names that convey different meanings that are often misunderstood and misrepresented.

There is a needless debate within some movements about supposed Babylonian origins of the upcoming Leviticus 23 Fall Feast, which goes by the names of Yom Teruah and Rosh HaShanah, but in reality, is never formally named in Scripture. Unlike Pesach (Passover), Shavuot (Pentecost), Yom Kippur (the Day of Atonement), and Sukkot (the Feast of Tabernacles), the first day of the Biblical month of Tishri is in many ways described but never actually named. It is described as a day of shouting or of the sounding of the shofar (translated “trumpet” in English), but it is never actually given a name–which is why it has been labelled by people with names suited to its function in both the religious calendar of months, and the agricultural/civic calendar of years. It therefore has no wrong names, just names that convey different meanings that are often misunderstood and misrepresented.

Yom Teruah, with Yom bearing the Hebrew meaning of “day” and Teruah being one of the sounds that is made with a shofar (an animal horn used as a “trumpet”, pictured above–this gorgeous specimen is an 18th century German shofar currently in use at the Great Synagogue at Duke’s Place in London). On this Feast Day, in the synagogues, the shofar will be blown 100 times, and I can tell you from the personal experience of having performed the entire liturgy on the shofar, it is exhausting and requires a lot of practice. It is a beautiful thing to hear.

The first day of Tishri is also called Rosh HaShanah, meaning “head” (rosh) of “the year”–and this is where the confusion comes in and accusations of pagan origins get made. So stick with me, the “year” beginning at this point, as opposed to the “months” beginning in the Spring, is actually documented both archaeologically and Biblically when we know what to look for. I am not going to go into every Biblical instance, because some of it requires more groundwork than I can lay out in a blog post of this nature, but I will tackle the verses that back up the specific archaeology I will cite here. All Bible references are from the English Standard Version.

Exodus 34:22 “You shall observe the Feast of Weeks, the firstfruits of wheat harvest, and the Feast of Ingathering at the year’s end.”

Lev 25:3-4 “For six years you shall sow your field, and for six years you shall prune your vineyard and gather in its fruits, but in the seventh year there shall be a Sabbath of solemn rest for the land, a Sabbath to the Lord. You shall not sow your field or prune your vineyard.”

Lev 25:8-11 “You shall count seven weeks of years, seven times seven years, so that the time of the seven weeks of years shall give you forty-nine years. Then you shall sound the loud trumpet on the tenth day of the seventh month. On the Day of Atonement you shall sound the trumpet throughout all your land. And you shall consecrate the fiftieth year, and proclaim liberty throughout the land to all its inhabitants. It shall be a jubilee for you, when each of you shall return to his property and each of you shall return to his clan. That fiftieth year shall be a jubilee for you; in it you shall neither sow nor reap what grows of itself nor gather the grapes from the undressed vines.”

So, we have a few things here, we see that the Fall Feasts are celebrated “at year’s end.” This Hebrew word is tequpat, from the lemma tequpah, and serves as the direct object of the sentence referring to the end of the agricultural year. Forms of this word are only used three other times in Scripture, referring to the end of Hannah’s pregnancy and the beginning of Samuel’s life in I Sam 1:20, the completion of the sun’s circuit to the end of the heavens in Psalm 19:6, and designating the timing of Joash’s assassination to the end of the year in II Chron 24:23. Each time it is used, it has the meaning of the ending of one cycle and the beginning of another–in the case of Ex 34:22, the end/beginning of the agricultural year which happened at the fall harvest and kicked off the “season of our joy” when all the hard work of the harvest year was done and all that was left to do was plant the new barley crop in anticipation of the early rains, and whatever preservation work was required for winter.

We also have a different kind of new year cycle celebrated in the month of Tishri, and that is the “shemittah” cycle. This referred to the seven-year cycles of the Land of Israel, which go beyond the scope of this particular teaching. Suffice it to say that each year in the seven-year cycle had specific commandments associated with it as far as the distribution of the second/third tithe. The seventh year, in particular, was associated with release from debts and a freedom from all agricultural labors. Every seventh seven years was even more significant as lands were restored to their original owners who sometimes had to sell them to pay off debts. This all formally began/ended at Yom Kippur, as we see in the above verses.

Tishri 1 was also the day that Israel’s kings had their official coronations, and they counted their reign years according to this yearly event. For example, if a king died in the month of Elul, the previous month, his son would take the throne and would count the remainder of the month as the first full year of his reign, just as his father also got a full year’s credit for that eleven month year before his death. But he would not have his coronation until Tishri 1–after all, that was when the animals were mature, the fattened calf was really fat and still a calf, all of the produce of Israel was available for the event. Who would want to have their coronation in the Spring when the only fresh crop was barley? Blech. Not really very glorious…

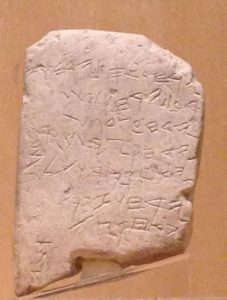

So, although we see in Ex 12:2 that we have the beginning of months in the Spring, marking the beginning of the religious year, the Israelites celebrated the beginning of actual years in the fall, according to an agricultural and civil schedule, as opposed to the Babylonians, who celebrated their New Year festival in Nisan. But wait–there’s more! I can actually show you archaeological proof, found in 1908 in a dig at ancient Gezer, 20 miles from Jerusalem. This 10th century BCE calendar (below), manufactured 200 years before the Assyrian exile and 400 years before the Babylonian exile, is a paleo-Hebrew witness of the ancient “year” calendar of the time of the Davidic Monarchy.

Here is the translation, courtesy of Rainey and Notley’s The Sacred Bridge: Carta’s Atlas of the Biblical World (it is the gold standard of Biblical atlases, generously donated to my ministry by my anonymous benefactor who I only know as Jennifer):

Line 1: His two months: Ingathering His two months: Sowing

Line 1: His two months: Ingathering His two months: Sowing

Line 2: His two months: Late Sowing

Line 3: His month: Chopping Flax (for grass)

Line 4: His month: Barley harvest

Line 5: His month: Harvest and measuring

Line 6: His two months: Vine harvest

Line 7: His month: Summer fruit

(signature) Abiya

Line one corresponds to the 6th through 9th months of the Hebrew calendar; line two to the late sowing of the 10th and 11th months; line three to the 12th; line four corresponds to the barley harvest of the first month, and line five to the second month. Line five refers to the vine harvesting of the 3rd and 4th months, and the seventh line wraps it up with the summer fruit harvest (specifically, olives). This is an agricultural calendar, arranging the months of the year according to what was happening in the fields. It begins with the “ingathering at the end of the year” referred to by Ex 34:22 and ends with the harvesting of the olives that would have been pressed and preserved as oil before the long winter months of rains and waiting.

Ancient people thought about the world differently than moderns. Whereas we think in terms of calendar years (Jan), fiscal years (April), election years (November), and school years (August/September), they thought in terms of religious, legal, and agricultural years. The religious year of “months” began in the Spring month of Nisan. The civil year of second tithe determination, debt remission and kingship began in Tishri, the seventh month in the Fall. The agricultural year began with the ingathering in the fall, as the Gezer calendar highlights.

And so, in the Fall, Tishri 1 can be called Rosh HaShanah, “head of the year” and be an entirely accurate description. Life radically changed in the fall, as the cycle of one agricultural and civil year ended and another began.

Now, as for the High Criticism claims that Rosh HaShanah has its origins and timing in the Akitu festival of ancient Babylon, I first need to explain what “higher criticism” is. Sadly, it was a method of Biblical criticism that was very popular in the eighteenth, nineteenth and early twentieth century but has now fallen into disfavor based on the windfall of archaeological evidence gathered over the last 150 years. “Lower” or textual criticism is a way of evaluating the Biblical text via actual documents–one can use it to evaluate textual differences between manuscripts. It is useful when manuscripts don’t match up exactly, as in the case between the modern Masoretic Hebrew Bible and the earlier manuscripts found in the Dead Sea Scrolls. But Lower criticism uses actual evidence. Higher criticism, on the other hand, is a very subjective approach to the text that is highly dependant on theories and sometimes, purely wishful thinking. Higher criticism is based on some pretty significant assumptions–and challenges the legitimacy and authorship of the Scriptures. According to much of higher criticism, the Torah was not written by Moses, who might have been nothing but a fictional character–but was penned during and after the Babylonian exile by various groups. Higher criticism is where the ideas of the “Deuteronomy hypothesis,” lunar sabbath, and the Babylonian Akitu origins of Rosh HaShanah came from. Higher criticism tends to want to find “natural” and “non-divine” origins in everything–it actively undermines the historical authenticity of the Bible’s claim that it was written when it was claimed to be written, and by who it was claimed to be written. Sabbath just has to be tied to ancient lunar cycles, it couldn’t possibly be divinely ordained, and the Feasts need to be explained away as copies of Canaanite celebrations, again, they can’t possibly be of divine origin. According to this line of thinking, the Jews in exile, desperately seeking to remain a people, wrote the Bible in order to give their beliefs more credibility. That is the nutshell view of higher biblical criticism. It has also greatly affected many teachings about the origins of Christianity, many of which are based on unproven or disproven theories.

Anyway, the idea that Rosh HaShanah is based on Akitu is completely unsubstantiated–purely theoretical. Not only is there no proof, but there are factors weighing against it. First of all, I have no reason to believe the Bible was first written during the exile. I believe that the Bible is telling the truth when it talks about Moses writing everything down. Heck, I believe that Moses, Aaron, Mirian, Abraham, Isaac and Jacob are real people. I believe they celebrated the Feasts, all of them, before the exile. I don’t think that the priestly class created the Bible as job security. You can call those wild assumptions, but I presume that no one would take the time to read this is they didn’t take the Bible as a truthful document.

Akitu was a twelve-day spring barley harvest festival dedicated to the state god Marduk. It began on the 21st of Adar and ended on Nisan 1 or on Nisan 1 and ended on Nisan 12 (there is some debate among scholars with most, I believe, favoring the latter). This was the “beginning of the year” in the Babylonian empire. As a matter of fact, the word akitu is related to the Sumerian word for barley–akiti. I am not going to go into a lot of detail about the Akitu festival, but to compare it to Rosh HaShanah and the accompanying shofar blowing and the liturgies–I just don’t see it. Akitu was in the spring, RH is in the fall. Akitu was a 12-day festival, and RH is one day. Akitu was about the barley harvest, the lowliest of the harvested crops, whereas RH was celebrated in the time of wine, oil, and late fruits. At Akitu, the king of Babylon was subjected to a debasing ritual (which involved him being stripped of all honor, dragged by the ear, and slapped, all grave insults in the ancient Near East), and RH has no such equivalent–on the contrary, it was the day of ancient Israel’s coronations. Akitu involved the parading around of the idol of Marduk, and on RH we see no evidence that there was any sort of equivalent.

In short, we need to be very wary of accusations over the “real origins” of this or that celebration or observance because we will oftentimes find the roots of such theories in the very higher criticism which has come under scholarly disfavor. Sadly, it was commonplace for people to float hypotheses as plausible when they really had nothing more than a supposition. Others who read them did not always realize that they were untested opinions and treated them as fact. Accusations are serious business, and should not be leveled without serious proof. It is not enough to assume that there might be pagan origins of this or that–we must know. The death penalty for idolatry in the Bible is death, and anyone who made an accusation without first-hand evidence would be put to death themselves. We have grown too lazy, and have taken our American concept of freedom of speech as a right to make accusations without any sort of proof. There is no proof whatsoever in the Babylonian origins theory of Rosh HaShanah, all we have are untested hypotheses that cannot be considered as anything more than opinions. So, perhaps it would be wise to drop the accusations and the vitriol, and simply be glad when people observe the High Sabbath of Tishri 1, honoring the King of Kings as a worldwide body.

Referenced works: (I am including some online sources that I have found to be reasonable–as many internet pages devoted to exploring paganism are not based on the ancient literature and archaeology but on modern legends, so let the reader beware–always make sure that actual experts in the field are being cited. For example, the opinion of a linguist is not the same as the educated conclusion of an archaeologist in some matters and the opinion of a numismatist would bear little weight in linguistics!)

Rainey, Anson, and Notley, Steven The Sacred Bridge: Carta’s Atlas of the Biblical World, Second Edition, Carta Jerusalem, 2014, pg. 42

(online sources on Gezer calendar here and here)

Van Der Toorn, Karel Dictionary of Deities and Demons in the Bible, Second edition, Brill, 1999, pp543-548

Oshima, Takayoshi, The Babylonian God Marduk from Leick’s The Babylonian World, Taylor & Francis, 2007 pp. 348-360

Sommer, Benjamin The Babylonian Akitu Festival: Rectifying the King or Renewing the Cosmos? Journal of the Ancient Near Eastern Society (JANES), Volume 27, 2000 – available online

(online sources on Marduk and Akitu here and here)

In the interest of fairness, I am going to include a resource that I treasure highly and did use quite a bit in my studies, but delves quite a bit into higher criticism of the origins of the festivals. It remains, however, the most brilliant work on the Psalms every written and is considered the definitive work by both Jews and Christians worldwide. I include it so that you can see how higher criticism is worked into the books published in the mid-twentieth century (in this case, first printing 1962). It does not, however, detract from his ground-breaking analysis of the Psalms themselves, and Mowinckel agrees that the Jewish tradition of RH being associated with kingship did not come from foreign influences (p. 123)

Mowinckel, Sigmund The Psalms in Israel’s Worship, Eerdmans, 2004 pp 106-192

Much needed info here! Thank you.

I have never heard of the Akitu origin of Rosh Hashanah. This explanation should put that thought to rest for some. Too many are searching for pagan influences in worship and less on What Is Written.

I agree–it robs people of their joy when everything is under suspicion. Having been susceptible to this line of thought in the past, I see it as the working of the Accuser in my life.

Great explanation.

Hello i was hoping to send for prayer for a true repentance heart this Yom Kimpper for me and my daughter and mother