Who was the Queen of Heaven and did she really dip eggs in the blood of infants? Jeremiah 7 in Context

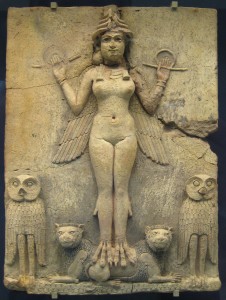

(Pictured, Ishtar as the evening star/patron goddess of love, war, and sexuality with her customary lion emblems as well as the owls who denote her position as patroness of prostitutes)

It has come to my attention that some folks are thinking that I am not aware that Ishtar is a pagan goddess. I reread my blog and I am seriously struggling to imagine why anyone would think that I am believing she is real. This is a Biblical context study and I am teaching the ANE (Ancient Near Eastern) context of who this Ishtar was who was being worshiped alongside God in His Temple. Please read it, and if you have any questions – check out the rest of my blog or give me the respect to ask me about it. I even mentioned Messiah in my blog. I don’t know how more clear I can be.

I am writing this as a follow up to my blog on Tammuz, and again, I post a plea for civility. I wrote a book that included the phrase “Ishtar Sunday” without doing my homework. Over 70,000 words of carefully researched Biblical references and I blew it simply repeating something that “everyone” knew. So many people who I respected as teachers and leaders over the last ten years had said it that I took its veracity for granted. The information I am presenting comes at a loss of face to myself, but only after a great amount of research into the archaeological and historical evidence we have on Ishtar and her worship in the fourth through mid-first millennium BCE. We have at our disposal epics and cult rituals in cuneiform tablets, carvings, steles, seals, contemporary descriptions of her cult from those during her time period, temples excavated – in truth we might have more information on Ishtar than any other Mesopotamian deity. We even know the minute details of her temple administration. She was the most beloved and powerful goddess in the Mesopotamian pantheon for thousands of years – even reaching into the Hebrew sphere at the height of Babylon’s Power in the mid-first millennium. We know who worshiped her and why, we know her spouses–men, gods, and even various animals. We know how her cult was celebrated, and how her priests were attired. We know more about her sex life than I wish we did. We know her cult symbols, and we have evidence of her cult throughout four separate millennia. I present this evidence as a mea culpa, admitting my complicity in perpetuating something I had not studied out myself. This presentation will be brief and will only cover the highlights–I could write a book on her but will refrain from doing so.

What I present might make you angry but I will give all of my sources, and if after going through them all you disagree with me then I can’t do anything about that, but I caution you not to react angrily to my honest findings. This is not presented against any ministry (except maybe my own), but in the pursuit of truth–which we must always search for and never settle for anything less or we are no better than any religion that we claim to be set apart from. Please remember that I am your sister, and not someone to be lashed out at. What I am going to present is as odds with Alexander Hislop’s The Two Babylons in every respect (see the Tammuz blog for more information on Reverend Hislop), in fact, I have found not even a shred of evidence of the claims that many ministries are making about her supposed connection to Easter rituals. If there was any truth in Hislop’s claims in the 19th century, then by now someone would have found something. His book was debunked in the 1920s and yet remains a favorite among those who want evidence against things that are associated with the Catholic Church. For the record, I have no love for the Catholic Church as they tossed my grandmother out on her ear after her husband abandoned and divorced her with three kids in the 1950’s–but I don’t hate them enough to not set the record straight. So, here is a brief summary of my findings followed by an extensive bibliography.

Ishtar (Akkadian) and Inanna (Sumerian) were different names of the same Mesopotamian goddess–she was the undisputed Queen of Heaven, no other goddess in any culture even came close to matching her prowess. She was originally the goddess of the storehouse and the fertility associated with it, became the goddess in charge of giving kings their authority, and in later days was the goddess of war, passion, and prostitutes. She was–as Inanna, portrayed as the virginal daughter and eager young bride, then as Ishtar, characterized by her long list of disastrous relationships (as detailed in the Gilgamesh epic where he lists her multiple paramours who came to bad ends). Her famous marriage to Dumuzi (Tammuz) under the name Inanna is sometimes portrayed in kind tones, as when he is killed by brigands who club him over the head while stealing his livestock, and sometimes in brutal tones, as when she contracts demons to steal him away to the Underworld in order to take her place after unsuccessfully trying to steal the Underworld throne from her sister! She either helps his sister, the goddess of vines, and mother search for her own murdered husband, or is the cause of his mother and sister searching for him.

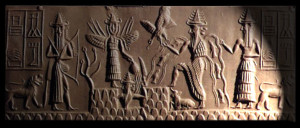

Strangely, in a world where goddesses are routinely portrayed as mothers – she is not. Ishtar is the virginal bride, or the passionate lover or in later times the patroness of prostitutes or–of transvestites! Here (to the left) we see her alongside the other gods of the Gilgamesh Epic.

Ishtar worship took various forms–she instituted wailing, perhaps on behalf of her husband Tammuz, as well as the ritual of sacred marriage when Mesopotamian kings would enact their royal marriage to Ishtar as a way to solidify their claim to the throne. In latter days, her priests would cross-dress and behave as transvestites during her very strange festivals–festivals that involved the playing of children’s games, and general age, status, and gender confusion. There was no impregnating of virgins, and Babylonian religion did not involve a human sacrifice in any accounts that I can come up with–despite having a wealth of information. And even if, at one point, it had included human sacrifice–Crassus outlawed it in the 90’s BCE throughout the Roman Empire and noted that it was only done before then rarely and in connection with the magic arts, not in the regular worship of gods or goddesses (Pliny the Elder, Natural History XXX). Human sacrifice was considered to be barbaric and “un-Roman,” the same attitude they had towards the practice of abortion. The Carthaginian worship of Cronos in Africa seems to be a notable exception within the Empire, and the Romans slandered them much for it.

Animal sacrifice was common in Ishtar worship–but then it was common in all forms of worship in the Ancient Near East and First Century. Gods and goddesses had temples for one primary reason–for their human servants to care for their physical needs while they performed their cosmic functions. Ishtar had to protect the King, she was the overseer of the storehouse, preventing starvation–if Ishtar had to spend time gathering food and drink for herself then she might become distracted and chaos would ensue. This was the ancient view of all of the worship of gods–to care for them. At the top of their ziggurat was a little home and inside there were rooms. The idol that provided access to the essence of the god was woken up in the morning, bathed and dressed in finery, fed the choicest portions, worshiped, and then put back to bed at night. As they cared for Ishtar, she was free to do her important job of caring for her functions in the universe. Animal sacrifice was simply a way to provide her with the food she needed to survive. She had no link to Sunday worship or festivals celebrated on that day–like all gods and goddesses, she was worshiped and cared for every single day. She did have two festivals that were celebrated at the rising and setting of the planet Venus in the winter and summer, eight months apart–being that she was also known as the morning and evening star.

Ishtar’s symbols were the lion and the six or eight-pointed star within a circle (which did not look like the star of David but more like a spiny starfish) and sometimes the eight-pointed star (the image to the left is not the best example, sadly, the British Museum has an excellent cylinder seal imprint but it is unavailable online). She is often pictured either standing on or riding a lion, or with a two-headed lion mace and a hooked sword called a harpe. She is never pictured with rabbits or eggs (which were not fertility symbols in the ancient Near Eastern world) nor do any of her rituals or legends make mention of them. She is often pictured in the nude, as the goddess of love and passion, or wearing a strange pointed hat (kinda like the 80’s band Devo) along with the weapons of war as the Lady of Battle. By the time of Messiah, Ishtar worship was pretty much nonexistent.

She is also never mentioned in reference to Semiramis, the 12th century Mesopotamian Queen who lived shortly before King David but who was not married to Nimrod, nor did she have a son named Tammuz – but that’s for a later blog.

Just for information sake – I do not use Herodotus as a reliable source for anything outside of Greek culture, as he was notorious for simply writing every second-hand story he heard. His writings on Egypt, for instance, have not only gone unsubstantiated but have been largely disproven.

I realize this is short, but Ishtar is far too complex to be covered adequately in a blog and it would be inappropriate to go into great detail anyway. You have my resources, listed below – pretty sure I put them all in but my library is quite the mess at the moment.

Bibliography

(these are all the books and articles I read, in addition to those related to Tammuz because all of the stories about him are also about her – be sure to hit every reference to Inanna, Ishtar (or Istar), Dumuzi and Tammuz. But let the reader be warned, Ishtar literature is often egregiously sexual in nature)

The Treasures of Darkness: A History of Mesopotamian Religion, Thorkild Jacobsen (Ph.D. Assyriology, the guy even taught at Harvard, during his lifetime and even now he is considered one of the foremost experts in the Ancient Near East)

The Babylonian World, Gwendolyn Leick, Ed – Chapters 7, and 22-24 were especially helpful.

A Dictionary of Ancient near Eastern Mythology, Gwendolyn Leick, (Ph.D. Assyriology)

The Ancient Near East: An Anthology of Texts and Pictures, James B Pritchard, Ed (all of Pritchard’s books have impressive pedigrees and this one is no different – being the work of seventeen serious ANE scholars)

The IVP Bible Background Commentary, John Walton et al. commentary on Ezekiel 8

Myths from Mesopotamia, Stephanie Dalley

Handbook of Life in Ancient Mesopotamia, Stephen Bertman

Interpreting the Past: Near Eastern Seals, Dominique Collon

The Ishtar Temple at Ninevah, Julian Reade, Iraq, Vol 67, No 1, Ninevah. Papers of the 49th Recontre Assyriologique Internationale, Part Two (Spring 2005) pp 347-390

Ishtar, the Lady of Battle, Nanette B Rodney, Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin (this can be found online if you search under title and author but as I have not seen any other serious articles or accounts equating Ishtar with Ashtoreth, let the reader beware on that one point)

Inanna-Ishtar as Paradox and a Coincidence of Opposites, Rivkah Harris, History of Religions, Vol 30, No 3 (Feb 1991), PP 261-278 (very good article, but rather shocking, details some of her riske festivals)

A New Ishtar Epithet in the Bible, Joseph Reider, Journal of Near Eastern Studies, Vol 8, No 2 (Apr 1949) pp 104-107

On the Entymology of Ishtar, George A Barton, Journal of the American Oriental Society, Vol 31, No 4 (1911) pp 355-358 (I include it because I read it but it is really only interesting if you are into linguistics)

The White Obelisk and the Problem of Historical Narrative Art of Assyria, Holly Pittman, The Art Bulletin, Vol 78, No 2 (Jun 1996), pp. 334-355 (only brushes on Ishtar, but if you are interested in Assyrian obelisks and first/second Millenium Assyrian archaeology, this is fascinating)

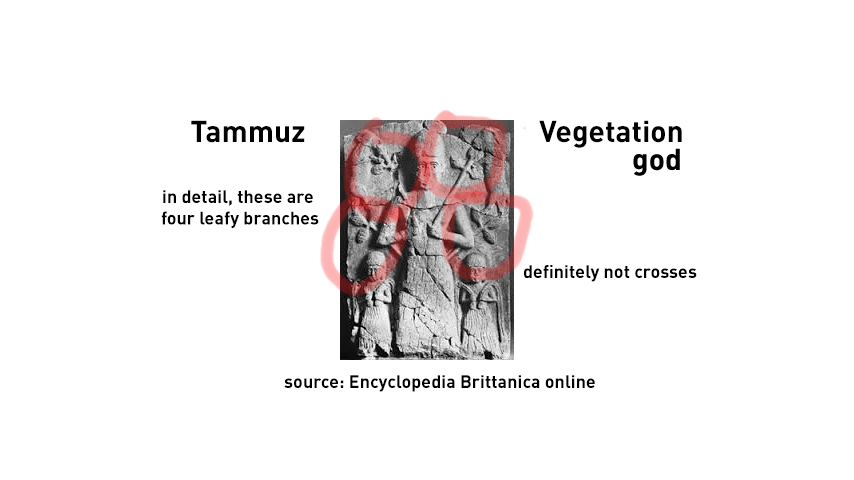

Toward the Image of Tammuz, Thorkild Jacobsen History of Religions, Vol. 1, No. 2 (Winter, 1962), pp. 189-213 (available on JSTOR.org)

Tammuz and the Bible (this one was great), Edwin Yamauchi, Journal of Biblical Literature Vol. 84, No. 3 (Sep., 1965), pp. 283-290 (also available on JSTOR.org)