Confronting the Memes Pt 7: Did Jeremiah condemn Christmas trees or are we being anachronistic?

One of the first memes I ever came across (and shared) was in reference to the “Christmas tree” described in Jer 10:2-4. I looked at the referenced verses, read nothing before or after and that was good enough for me. Years later, while studying the entire chapter, I realized that I had perpetuated an “anachronism” on the text and simply stopped sharing such things. Over the last two weeks, however, I ran into multiple Ancient Near Eastern documents describing the very same phenomenon we see in Jer 10:1-15 and using almost the same exact wording – one in a Babylonian epic and the other in a Hittite document. Added to that, I received a request from a facebook friend wondering about a meme she had recently seen on this subject. She wanted to know if she could or could not share it with integrity. So, I took the hint and decided to go ahead and work up this blog post. I get nervous about posting about Christmas too close to Christmas when emotions on both sides of the argument are running too hot for most folks to think straight. As soon as people get invested with posting pro and anti-Christmas memes, this kind of a blogpost can get dangerous and instead of weighing the evidence, insults can start flying.

One of the first memes I ever came across (and shared) was in reference to the “Christmas tree” described in Jer 10:2-4. I looked at the referenced verses, read nothing before or after and that was good enough for me. Years later, while studying the entire chapter, I realized that I had perpetuated an “anachronism” on the text and simply stopped sharing such things. Over the last two weeks, however, I ran into multiple Ancient Near Eastern documents describing the very same phenomenon we see in Jer 10:1-15 and using almost the same exact wording – one in a Babylonian epic and the other in a Hittite document. Added to that, I received a request from a facebook friend wondering about a meme she had recently seen on this subject. She wanted to know if she could or could not share it with integrity. So, I took the hint and decided to go ahead and work up this blog post. I get nervous about posting about Christmas too close to Christmas when emotions on both sides of the argument are running too hot for most folks to think straight. As soon as people get invested with posting pro and anti-Christmas memes, this kind of a blogpost can get dangerous and instead of weighing the evidence, insults can start flying.

First of all, let’s look at Jeremiah 10 in context – it is a conversation between YHVH and Jeremiah the prophet. On one hand, we have God denouncing something, and on the other hand we have Jeremiah exalting God over whatever it is that He has been denigrating. But what is God denigrating? Is it an ancient Christmas tree? In fact, do any of the images we have from archaeological finds represent Christmas trees or do they actually depict an entirely separate thematic element? (This is the point in the blog where I make it clear that I do not celebrate Christmas – God gave us feasts, Messiah kept them and I follow Him by doing as He did. Too many traditions associated with Christmas fall into the “hinky” category and I celebrate Messiah’s birth on the Biblical feast of Sukkot, which was the actual day of His birth. As much as I disapprove of Christmas, I abhor any attempt to twist the Scriptures into saying something that they do not say – the ends never justify the means when the means is playing fast and loose with the Word of God – it hurts our witness when the truth does eventually come out).

I am going to remove Jeremiah’s words, and just focus on what God is saying in order to make things clearer but I encourage you to read the entire passage in context:

Hear the word that the LORD speaks to you, O house of Israel. Thus says the LORD:

“Learn not the way of the nations, nor be dismayed at the signs of the heavens because the nations are dismayed at them, for the customs of the peoples are vanity. A tree from the forest is cut down and worked with an axe by the hands of a craftsman. They decorate it with silver and gold; they fasten it with hammer and nails so that it cannot move. Their idols are like scarecrows in a cucumber field, and they cannot speak; they have to be carried, for they cannot walk. Do not be afraid of them, for they cannot do evil, neither is it in them to do good.”

They are both stupid and foolish; the instruction of idols is but wood! Beaten silver is brought from Tarshish, and gold from Uphaz. They are the work of the craftsman and of the hands of the goldsmith; their clothing is violet and purple; they are all the work of skilled men.

Every man is stupid and without knowledge; every goldsmith is put to shame by his idols, for his images are false,

and there is no breath in them. They are worthless, a work of delusion; at the time of their punishment they shall perish.”

The main problem I have with these memes equating these verses with a condemnation of Christmas trees (when nothing of the sort existed during that time period and so there was not yet any reason for such condemnation) is that they conveniently all cut off at verse four – when verse five gives the context as being specifically about the making of idols. When you learn about Ancient Near Eastern idolatry, the subsequent verses about beaten silver and gold, and the fine clothing offer an even more glaring indictment of the comparison to this passage being about decorated trees. And scarecrows are not trees – they are meant to look like men. Can you imagine a crow being scared of a Christmas tree in the field? Or it being necessary to point out that a tree cannot speak, or that it can’t walk? How about the “instruction of idols”? – That refers to the priests going before an idol and asking it questions through divination. No one does that with a Christmas tree. So let me teach you about how to make an worship an idol – lol, I know that sounds bad but everyone in the ancient Near East knew this material that God was making reference to. I am not teaching you so that you will be able to do it, but so that you will get the reference being made.

Let’s add a similar reference from Isaiah 44:9-20, which also explicitly refers to the making of an idol:

All who fashion idols are nothing, and the things they delight in do not profit. Their witnesses neither see nor know, that they may be put to shame. Who fashions a god or casts an idol that is profitable for nothing? Behold, all his companions shall be put to shame, and the craftsmen are only human. Let them all assemble, let them stand forth. They shall be terrified; they shall be put to shame together.

The ironsmith takes a cutting tool and works it over the coals. He fashions it with hammers and works it with his strong arm. He becomes hungry, and his strength fails; he drinks no water and is faint. 13 The carpenter stretches a line; he marks it out with a pencil.[a] He shapes it with planes and marks it with a compass. He shapes it into the figure of a man, with the beauty of a man, to dwell in a house. He cuts down cedars, or he chooses a cypress tree or an oak and lets it grow strong among the trees of the forest. He plants a cedar and the rain nourishes it. Then it becomes fuel for a man. He takes a part of it and warms himself; he kindles a fire and bakes bread. Also he makes a god and worships it; he makes it an idol and falls down before it. Half of it he burns in the fire. Over the half he eats meat; he roasts it and is satisfied. Also he warms himself and says, “Aha, I am warm, I have seen the fire!” And the rest of it he makes into a god, his idol, and falls down to it and worships it. He prays to it and says, “Deliver me, for you are my god!”

They know not, nor do they discern, for he has shut their eyes, so that they cannot see, and their hearts, so that they cannot understand. No one considers, nor is there knowledge or discernment to say, “Half of it I burned in the fire; I also baked bread on its coals; I roasted meat and have eaten. And shall I make the rest of it an abomination? Shall I fall down before a block of wood?” He feeds on ashes; a deluded heart has led him astray, and he cannot deliver himself or say, “Is there not a lie in my right hand?”

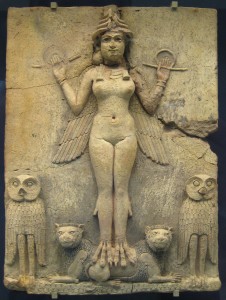

Most people only saw the city idols at a festival, otherwise, they had their own small teraphim at home – small ancestral gods which I will discuss some other time as they are entirely different. The city gods “lived” within their respective temples, called their house, as we see in Isaiah – or rather, their idol did. The idol was not believed to be the god himself, but instead was believed to be sort of a conduit. The essence of the god could enter in to the idol in order to be cared for.

What? A god or goddess that needs TLC? Yes, actually that was the main purpose of the pagan temple. Within the Temple was a house and a human staff to run it. The idol had a bed, was woken, bathed and dressed in the morning, then stood up to be fed through food and drink offerings, was enthroned all day before being undressed and put back to bed at night. The only change to this routine was during festivals where it would be carried through the city, its hand held by the King. We see this same routine in the records of Egypt, Hattiland (Hittites) and Babylon.

Now how was an idol made? We see this in The Babylonian Erra Epic (aka Erra and Ishum) – Tablet 1 contains the following imprints. In context, Erra, the warrior god, is challenging Marduk, the king of the gods, because the idol (image) in his temple had lost its luster. Marduk explains that he left his dwelling when he caused the great flood. Everything in () is my commentary.

(Marduk speaking)

“As to my precious image (aka idol), which has been struck by the deluge that its appearance was sullied

I commanded fire to make my features shine (because it is overlaid with gold) and cleanse my apparel (evidently it wears clothing)

When it had shined my precious image and completed the task

I donned my lordly diadem and returned…. (when his idol looked suitable again, he returned his essence to it)

…I sent those craftsmen down to the depths, I ordered them not to come up

I removed the wood and gemstone and showed no one where…..

Where is the wood, flesh of the gods, suitable for the lord of the universe, (every culture I have come across seemed to believe that only certain kinds of wood were suitable to be the “flesh” of an idol – in this case, the wood is from the “mesu” tree)

The sacred tree, splendid stripling, perfect for lordship,

Whose roots thrust down a hundred leagues through the waters of the vast ocean to the depths of hell,

Whose crown brushed Anu’s heaven on high?

Where is the gemstone that I reserved for {damaged}?

Where is Ninildum, great carpenter of my supreme divinity, (Ninildum is the idol maker)

Wielder of the glittering hatchet, who knows what tool, (although we would think of a hatchet only in the hands of a lumberman, in this case the hatchet is the tool of a crafsman – hatchets are way smaller than axes)

Who makes it shine like the day and puts it at subjection to my feet?

….

Where are the choice stones, created by the vast sea, to ornament my diadem?” (big city gods were crowned with real crowns just as they were dressed with real clothing)

Now, Herodotus claimed that Marduk’s idol was made of solid gold, but like too much of the information he recorded about cultures other than his own, he has been proven wrong through archaeology. His stuff on Greece is great – Egypt and the other ANE cultures, not so much – the guy seemed to pretty much believe everything people told him and he wrote it down. What we know from archaeology is that the large cult statues had a center core of “divine” wood overlaid with hammered precious metals, set with precious stones and dressed in the richest of clothing. As I mentioned before, no one thought that this was actually “the” god, but simply a representation so that the people of the city could care for the god’s basic needs of food, drink and shelter. Although we are accustomed to a God who needs none of that, it was their belief as evidenced in the Atrahasis epic and many epics that without humans the gods would actually starve and the universe would fall into chaos because they wouldn’t be able to do their jobs.

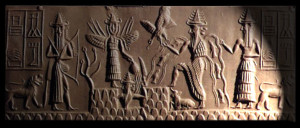

It was in the Akitu barley harvesting festival in the spring (end of Adar/early Nisan) that the idol of Marduk would be carried out of his temple and paraded through the city, with the king holding his hand as the procession made its way through the throng of gathered worshipers. This is the only time that anyone other than the temple staff would see the idol.

We also see this in the Hittite culture. Trevor Bryce writes, ‘In the latter part of the New Kingdom, the statues of the gods set up on bases in the sanctuaries of their temples were life-sized or larger. They were made of precious and semi-precious metals – gold silver, iron, bronze – or else of wood plated with gold, silver, or tin and sometimes decorated with precious materials like lapis lazuli.’ We have actual information on the statuette of the goddess Iyaya, ‘The divine image is a female statuette of wood, seated and veiled, one cubit (in height). Her body is plated with gold, but the body and the throne are plated with tin.’

So now we look back at Jeremiah 10, and we see that everything Jeremiah described was the common practice of the heathens of the day in how they made and treated their graven images. Even without this information, within the context of the entire chapter we see it cannot be about an anachronistic Christmas tree.

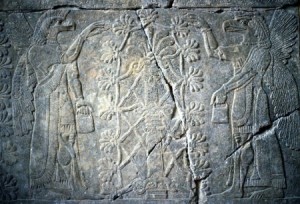

“But wait!” you might ask – what about all the cylinder seals and carvings of men worshiping before pine trees? Well, they aren’t pine trees and in fact every single one of these pictures that are used to promote the idea that Christmas trees are ancient are actually depicting the tree of life motif. Every culture had a creation story, about 1% have a flood story, and a great many have tree of life motifs. Life the flood and creations myths of other cultures, the tree of life had also been perverted – the Mesopotamians often portrayed it as being magically fertilized by Genies holding something that looks much like the citrons grown all throughout the region. Yes they are trees that look like pine – but if you were going to carve a tree that is as abundant as possible (as the tree of life would be), it would have fruit from top to bottom and stylistically would have to still leave room for figures depicted all around it. These trees have a great deal of palm tree in their artistic workup. For me, I think it’s kinda funny that they figured a divine tree needed pollination but then, they worshiped gods that needed to be fed and bathed – so par for the course, it’s how their minds worked.

“But wait!” you might ask – what about all the cylinder seals and carvings of men worshiping before pine trees? Well, they aren’t pine trees and in fact every single one of these pictures that are used to promote the idea that Christmas trees are ancient are actually depicting the tree of life motif. Every culture had a creation story, about 1% have a flood story, and a great many have tree of life motifs. Life the flood and creations myths of other cultures, the tree of life had also been perverted – the Mesopotamians often portrayed it as being magically fertilized by Genies holding something that looks much like the citrons grown all throughout the region. Yes they are trees that look like pine – but if you were going to carve a tree that is as abundant as possible (as the tree of life would be), it would have fruit from top to bottom and stylistically would have to still leave room for figures depicted all around it. These trees have a great deal of palm tree in their artistic workup. For me, I think it’s kinda funny that they figured a divine tree needed pollination but then, they worshiped gods that needed to be fed and bathed – so par for the course, it’s how their minds worked.

I could pull up a ton of others, notably from the palace of Ashurbannipal, as well as Egyptian examples, there are a great many. There is an interesting feature within google that might be helpful when people post such pictures and attribute them falsely. When you are in Google Chrome, you can actually “right click” on a pic and you will see “search google for this image” which will often lead you to a museum site which will tell you exactly where the image is from and what it depicts. That helps because we like to look at a picture and imagine what it means to us instead of finding out what it actually did mean to ancient peoples.

The Holy Bible: English Standard Version. (2001). (Je 10:1–15). Wheaton: Standard Bible Society.

Oshima, Takayoshi The Babylonian God Marduk (Chapter 24 of The Babylonian World, Gwendolyn Leick, ed) pp 355-6

The Erra Epic

Bryce, Trevor Life and Society in the Hittite World, p 157

Walton, John H Ancient Near Eastern Thought and the Old Testament, pp 116-7

Walton, John H et al The IVP Bible Background Commentary: Old Testament